Table of Contents

Pursuing a career in film music requires careful consideration. Being freelance alone is tricky, the chances of making a living in music are few, and the opportunities to do so as a film, TV, or game composer are even fewer. In this article I will take a look at my own career path, examine some of the essential skills, the mistakes I think I made, and consider some of the challenges of this career path and future threats to the industry.

Mark Slater: An Unexpected Career

I began delving into music technology and composition for film and television in the early 1990s. Prior to this I had had an excellent education in “classical” music, singing, playing the violoncello, piano, organ, in choirs, orchestras, quartets. I had dabbled in composing concert pieces for choirs, string quartets, organ, and the symphony orchestra.

During the 1980’s computers were just bringing to make their presence felt in schools and at home. So although I’d been excited by the pro audio recording and filming technology I saw during 5-years as a choirboy at Christ Church, Oxford, and attempted in my teens to record my father’s church choir and orchestra with two microphones and a Sony tape machine, and nearly chose the Tonmeister Degree course at Surrey University, I was actually slow to the world of professional music production technology. In addition, far from being sure about a career in music, I learned, once I left Oxford at age 13, that I was a mediocre talent in music, and lacked the intelligence and physical abilities to be a truly fine musician in any genre.

From the start of my consciousness on this planet, I have been surround by music and music making. I have very early memories of attending a concert hall full of people who had gathered to hear an orchestra and Paul Tortelier perform the Dvorak Cello Concerto. I remember discovering the Walton Cello Concerto on LP, and requesting to listen to it at the Sutton library in Surrey, UK. My father played the piano often, so I frequently heard him practicing Chopin, Brahms, Schumann, et al. and also witnessed him prepare to give music lectures and teach at the Royal College of Music, London. As a youth, I became obsessed with music and the subtle nuances of human performance breathing life and meaning into the dots, circles, numbers and lines of European musical notation. I listened to and performed Chopin, Messiaen, Nielsen, Sibelius, Richard Strauss, Tchaikovsky, Brahms, Bach, Verdi, Wagner, Puccini, Mozart, Bach, Handel, Vivaldi, Elgar, Prokofiev, Hindemith, Shostakovich, John Adams, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, ABBA, Genesis, Nick Kershaw, Tears for Fears, Simple Minds, Elton John, Billy Joel, The Smiths and Morrisey, to name only a few of my youthful favourites.

Embarking on a career journey within the highly competitive realm of film music, was in fact far beyond my ability to even hope, yet I began to dream of it once I became aware of the magic that music and composers brought to commercials, films, tv, and radio underscoring science fiction, fantasy, adaptations of classic fiction and plays, spy thrillers, detective stories, action movies, horror, psychological thrillers. The incredible score by Richard Rodney Bennett for Murder on the Orient Express; the dazzling orchestrations of Herbert W. Spencer in Clash of the Titans; John Williams in [Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T., Hook, Close Encounters, Jaws, Star Wars]; Vangelis in Blade Runner; Jerry Goldsmith in [Alien, Poltergeist, Star Trek]; Wilfred Josephs for I, Claudius; Barrington Pheloung for Morse; The Clangers; Blake’s Seven; Doctor Who. Since then, I’ve come to appreciate so many, many more musicians and composers.

After completing a Law degree, I took a chance on developing competency in music composition while working as a support worker for ex-offenders at a halfway house with a notable history: Norman House. While sharing a house in London’s Ealing district with a Glaswegian called John, another enlightened fellow from the north of England called Simon (who became my boss at the halfway house) I purchased a computer, sequencer software called Cakewalk, the Emu Proteus/2XR orchestral tone module, an ART 1U reverb unit with send and return cables, and started building the skills to use the rich combination of instruments in the orchestral palette to create colors and feelings with music.

My first efforts with the sequencer were transcribing favorite scores from music I was listening to at the time: Rimsky-Korsakov, Brahms, Wagner, Cliff Eidelman’s score for Star Trek VI. The process gave me instant feedback on what worked and how things were written effectively for all the instruments of the orchestra. However, my own attempts at composition were truly awful, pitifully short statements that copied other composers more than displayed any original synthesis of the music I knew.

In 1997, after a nearly 2-year mental collapse from work and loneliness in life, I discovered a new lease of positivity in a wonderfully talented and beautiful Italian woman, who helped me to reveal my secret feminine side, and encouraged me back to the stage, singing in musicals, taking on roles in straight plays, and eventually applying to join a Master’s Degree program held at Ealing Film Studios for Composition for Film and TV. During that year, I even relearned how to play the piano, and completed a seemingly impossible challenge of learning to play Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, for a concert performance with my father’s orchestra in 6 months.

At the London College of Music and Media, I took lessons with TV and brass band composer Rodney Newton, Nick Ingman, and was mentored by Martin Ellerby. I learned many techniques of the studio, digital audio production as it was at that time (ADAT tapes and hardware samplers), as well as scoring to picture, conducting, orchestration, and publishing. Afterwards, I returned to work at the halfway house, and slowly built up my usefulness for the non-profit, that I took over management of several residential services.

It took another 9 years before I got an email from a major agency Tribal DDB in New York asking me if I would be available to score an interactive flash-based website promoting the launch of the Philips Aurea with Ambilight technology. I think it was mostly luck that my own website, which I had paid a professional to design, had a color scheme that matched the creative teams plans for the commercial site. Consequently, I got my first chance to record at the globally-renowned Abbey Road Studios. Now, I had my music performed by some of the top session players in London, recorded and mixed by Andrew Dudman in Studio 1.

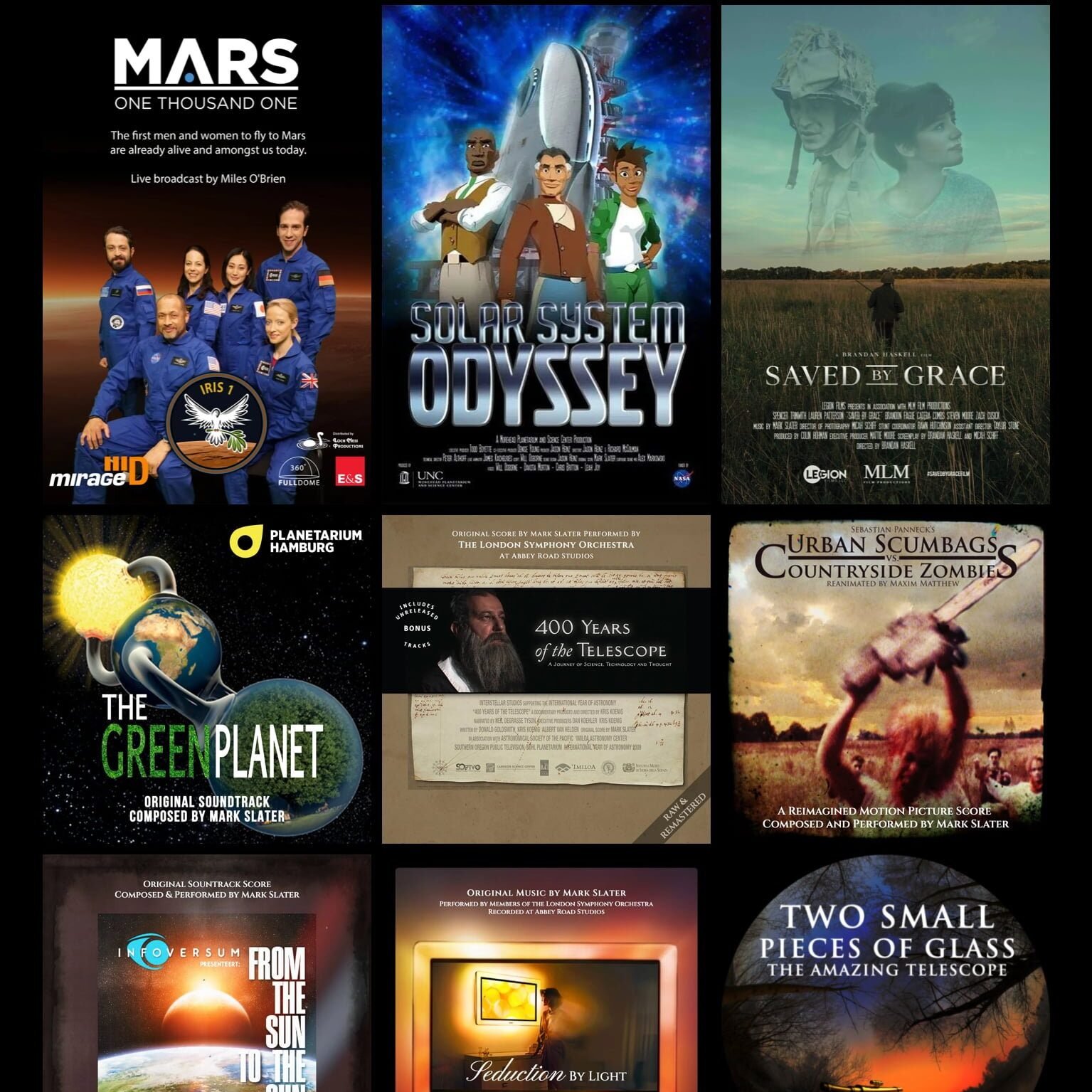

Following on from that, the next year I was invited to pitch for a major documentary film about the history of the telescope for the upcoming International Year of Astronomy. This time I won my place to score it presenting a musical approach to a section of the film’s narrated story, followed by an interview with an eminent scientist, discussing the Challenger disaster, the problems with the Hubble Space Telescope, and then the wonders revealed when Hubble was fixed by another space shuttle mission.

Charting Your Path: Steps to Become a Film Composer

Beyond having a knack for music or a degree in composition, the success of a film composer hinges on several key elements. First and foremost, aspiring film composers must develop an intimate understanding of different film genres, directing styles, and storytelling techniques. This deep knowledge is a prerequisite to creating a musical score that can effectively support the emotional narrative of a film.

Embracing the Future: The Role of Technology in Modern Film Composition

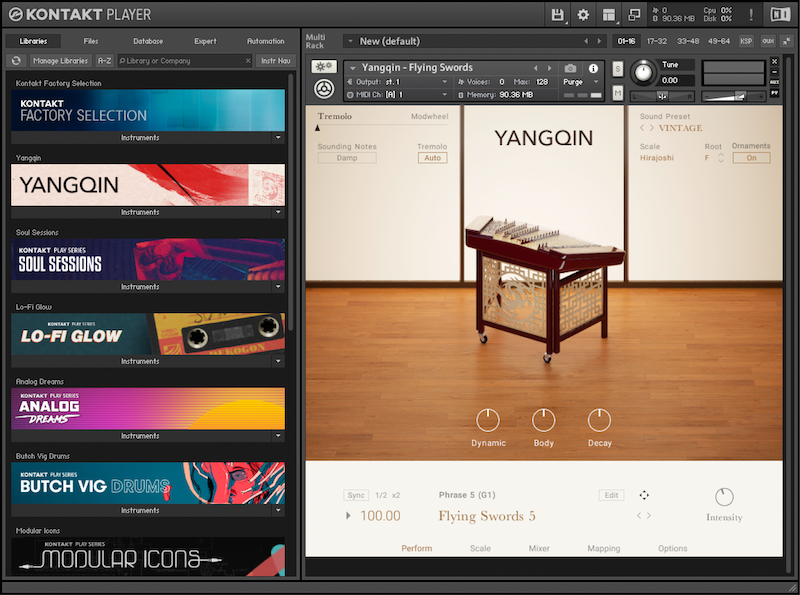

In this modern era, Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) have evolved to become crucial resources for film composers. Parallelly, the advent of notation software like Sibelius and Dorico has eased the task of generating professionally rendered music for recording sessions. Yet, the endeavor of composing music still remains a labor-intensive and strenuous process. But some of this may soon change due to Artificial Intelligence applications.

I anticipate that Artificial Intelligence (AI) will progressively carve out a more prominent role within music production. This transformation entails AI not merely crafting preliminary melodies or harmonizing tones, but also the meticulous generation of highly realistic instrumental ensemble mock-ups, attainable with a mere touch of a button.

For those who aspire to score films, this evolving landscape clearly implies an imminent challenge. The demand for their expertise and skills may dwindle, as film directors – with little to no training in music – might find themselves adequately equipped to underscore their own projects.

Educational Preparations: The Must-Have Degrees for Aspiring Film Composers

At present, the cornerstone of any budding film composer’s skill set is a comprehensive understanding of music theory, harmony, and counterpoint — all crucial elements that breathe life into the mysteries of different film genres. Equally essential are the technical skills in mixing, producing, and mastering, not to mention the age-old art forms of music notation, conducting, and playing musical instruments.

Academic establishments, notably colleges and universities, offer a myriad of courses geared towards film music. These educational opportunities are the foundations upon which one can amass rudimentary experience and knowledge in this specific field. Furthermore, affiliations with these institutions often facilitate budding composers’ first stints at scoring for films, often orchestrated in collaboration with film students. This networking within the academic environment can also pave the way towards internships with eminent studios and professional composers – a step that could significantly propel one towards a promising career in film music.

Ultimately, aspiring composers need to cultivate an ability to produce music from their personal systems that not only boasts a professional sound but also captures the essence of contemporary film music trends. In raw terms, they need to transcend mediocrity. The field is intensely competitive, with scant opportunities available; only those with an unyielding determination and an extraordinary talent stand a chance to emerge victorious.

Challenges Faced and Triumphs Celebrated: Mark Slater’s Career Highlights

Embarking on increasingly illustrious ventures, I have experienced a proportional surge in pressure. Undeniably, one of the pivotal responsibilities in any project is to effectively translate the director’s ambitious concept into a suitable and stylistically aligned musical score. The challenge broadens with every project, compelling me to ask questions as to my skills and music; taste. What was once a triumph in creation of a 45 minute score to the documentary 400 Years of the Telescope recorded by the London Symphony Orchestra at Abbey Road, soon became a testament (at least to my ears) to a lack of preparation, competency, and imagination.

While the score for this film was celebrated within its intended audience, it faced scrutiny among segments of the mainstream film production sphere. Nevertheless, this professional endeavor opened a door into an another realm of production, immersive media such as 360 digital video films for full dome theaters, planetariums, and bespoke film and experiential formats for themed entertainment. The following year I had another chance to record and conduct an original orchestral soundtrack score, this time recorded in Budapest, for a film about Charles Darwin’s exploration of the Galapagos Islands and theory of Natural Selection.

“You need to make peace with the fact that you’re going to create something that some people will passionately dislike. Embrace it, learn from it, and let it propel you forward into becoming a better composer,”

The Unseen Maestro: Impact of Film Composers on Cinematic Experience

Renowned film composers like John Williams, James Horner, and Jerry Goldsmith, to mention but a few, have irrefutably crafted our collective consciousness through their evocative melodies and resonant film scores. While there’s no denying their intense dedication to their craft, one cannot overlook the element of chance—the fortuitous combination of being in the perfect place at the most opportune moment—that propelled them to the pinnacle of their profession.

Pingback: Seduction by Light - Philips Aurea Campaign - Mark Slater