Writing atonal music can be a challenging and exciting endeavor. Atonal music, characterized by the absence of a tonal center or key, offers composers a unique opportunity to explore new and unconventional sounds. In this blog post, we will discuss some tips and techniques to help you approach atonal music writing for an orchestra.

Table of Contents

1. Writing Atonal Music

Before diving into writing atonal music for an orchestra, it is essential to familiarize yourself with the genre. Take the time to study and analyze the works of renowned atonal composers such as Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern. Pay attention to their use of dissonance, unconventional harmonies, and intricate orchestration. Understanding the techniques employed by these composers will provide you with a solid foundation for your own atonal compositions.

Atonal music, in its most basic essence, breaks away from the traditional tonal center, the ‘home base’ note, if you will, which is prevalent in most musical works. The root of the word “atonal” can be broken down into “a”, meaning without, and “tonal”, referring to tone, i.e., it’s music without a tonal center.

In atonal compositions, there is an egalitarian treatment of the 12 pitches of the chromatic scale; no single note dominates or serves as a focus point. This allows you to use any pitch at any time, giving you the freedom to explore pitch relations outside the confines of traditional tonal harmony.

The development of atonal music in the early 20th century was a response to the increasing chromaticism of the late Romantic era, which had pushed the boundaries of tonality to their limit. Instead of relying on established harmonic progressions, composers like Schoenberg initiated a method called twelve-tone technique or serialism, a system where all twelve tones of an octave are treated as equal with no distinction between a melody and accompaniment. Rather, the emphasis is on note-to-note progression.

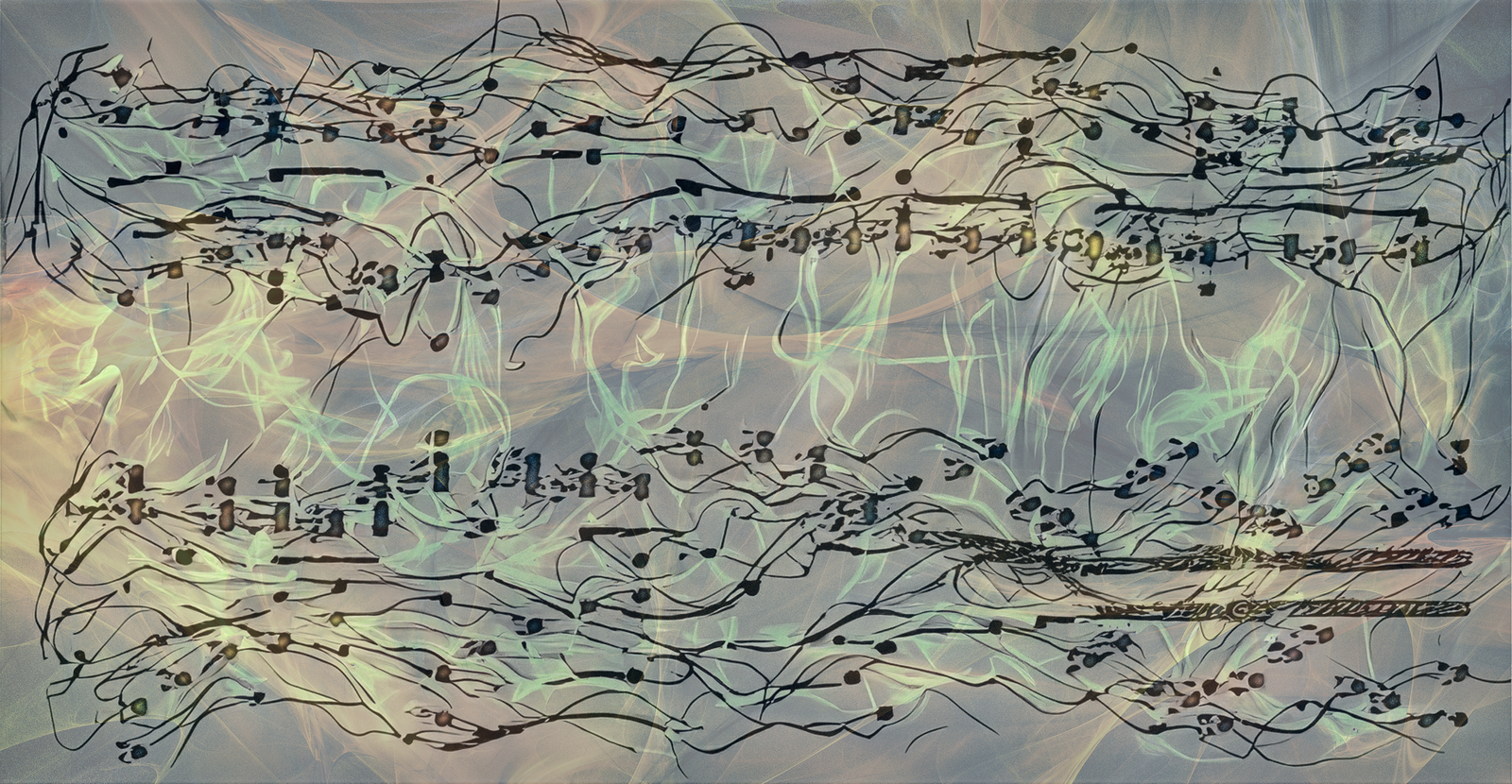

Remember, writing atonal music is an exercise in balance, texture, and the relationship between pitches. So, as you embark on your own atonal journey, let your imagination run wild. Play with pitches, think of the orchestra as a palette of sounds, and focus on creating a dense and diverse sonic landscape.

2. Experiment with Pitch Organization

In atonal music, there is no hierarchical organization of pitches based on a tonal center. Instead, pitches are treated as equal entities. Experiment with different pitch organization techniques such as serialism, where a specific ordering of pitches is used throughout the composition. You can also explore other methods like pitch-class sets or tone rows. These techniques will help you create a sense of cohesion and structure in your atonal compositions.

Serialism is an innovative method of writing atonal music that employs a series or row of musical elements to provide structure to a piece. This approach was pioneered by composers like Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and Alban Berg in the early 20th century, and has since been elaborated upon and developed by countless others.

In practice, serialism involves the arrangement of musical elements such as pitch, duration, dynamics, and even articulation into a predetermined series. This series is then applied to the total musical fabric. By doing so, serialism introduces a level of organization and logic that can be immensely helpful when composing within the atonal paradigm.

Moving onto the concepts of twelve-tone technique, a subset of serialism, it involves ordering all twelve pitches of the chromatic scale into a tone row. This row serves as the primary musical material of your composition, replacing traditional themes or motifs. Each pitch occurs once before the row is repeated, ensuring all twelve pitches have equal importance in your piece.

The resulting twelve-tone row can be manipulated through inversion, retrograde, and transposition, offering many avenues for thematic development. This technical method enhances consistency, creativity, and the ability to weave intricate and complex musical narratives.

Both serialism and the twelve-tone technique demand a strong sense of creativity and critical acuity. So it’s helpful to thoroughly practice these methods, and perhaps even write a few exercises using them, before incorporating them into your larger works.

3. Explore Timbral Possibilities

When writing atonal music for an orchestra, it is crucial to explore the vast timbral possibilities of each instrument. Experiment with extended techniques, such as col legno, sul ponticello, or multiphonics, to create unique and unconventional sounds. Utilize the full range of each instrument to add depth and complexity to your compositions. Remember that atonal music allows you to push the boundaries of traditional orchestration and explore new sonic landscapes.

Extended techniques, such as flutter tonguing on wind instruments or col legno on string instruments, are commonly used in atonal orchestral music.

4. Consider Texture and Form

Texture and form play a vital role in writing atonal music. Experiment with different textures, such as thick or sparse orchestration, to create contrasting moments within your composition. Consider the overall form of your piece and how different sections relate to each other. Atonal music allows for a wide range of possibilities in terms of form, so feel free to experiment with unconventional structures and transitions.

Structuring atonal compositions can often feel like navigating through a maze with no exit—a labyrinth of endless possibilities. But don’t be daunted! It’s this infinite plane of choices that makes atonal music uniquely expressive and profound.

When composing, think of the overall structure as a vast, unexplored landscape, and your musical ideas as your guiding compass. While atonal music frees you from traditional tonal relationships, it doesn’t mean that your compositions should be devoid of structure. Quite the opposite—in the absence of a tonal center, other musical elements need to fill the organizational void.

Work with motifs and thematic units—repetitive patterns that create a sense of unity and coherence. Thread these motifs through your composition like a common thread, tying different sections together. This can give listeners scattered islands of recognition in an unfamiliar atonal sea—little echoes that shout back from the void, making your composition more engaging.

Consider varying your motifs by applying techniques akin to those found in tonal music, such as inversion, retrograde, transposition, and augmentation. The use of these techniques will give your composition a sense of direction and structure that listeners can grasp, even amid the atonal chaos.

Also, ponder the emotional journey you want your listeners to embark upon. Should they start in a place of tension, venture into mystery, and land in celebration? Or should they traverse a serene dreamscape that spirals into an unsettling resolution? Use elements like dynamics, rhythm, texture, and timbre to shape this emotional arc, driving your piece forward and infusing purpose into every twist and turn.

Above all, remember that the key to structuring atonal music lies not in strict adherence to rules, but in creativity and emotional expression. So, let your instincts guide you towards a structure that best serves your artistic vision. Your orchestra is your canvas, the musical notes your palette, and the soul of your composition the masterpiece that emerges from it all!

5. Collaborate with Musicians

Collaboration with musicians is an excellent way to gain insights and feedback on your atonal compositions. Work closely with orchestral musicians to understand the technical and expressive capabilities of each instrument. They can provide valuable input on the playability and effectiveness of your writing. Additionally, consider attending rehearsals or workshops where your compositions are being performed. Observing the interaction between the conductor, musicians, and your music can provide valuable insights for future compositions.

6. Embrace the Unexpected

One of the most exciting aspects of atonal music is its ability to surprise and challenge the listener. Embrace the unexpected and allow yourself to take risks in your compositions. Don’t be afraid to explore unconventional harmonies, dissonant intervals, or unexpected rhythmic patterns. Pushing the boundaries of traditional tonality can lead to innovative and captivating musical experiences.

Writing atonal music for an orchestra requires a willingness to explore new sounds and techniques. By studying atonal music, experimenting with pitch organization and timbral possibilities, considering texture and form, collaborating with musicians, and embracing the unexpected, you can approach atonal music writing for an orchestra with confidence and creativity. So, go ahead and embark on this exciting musical journey!