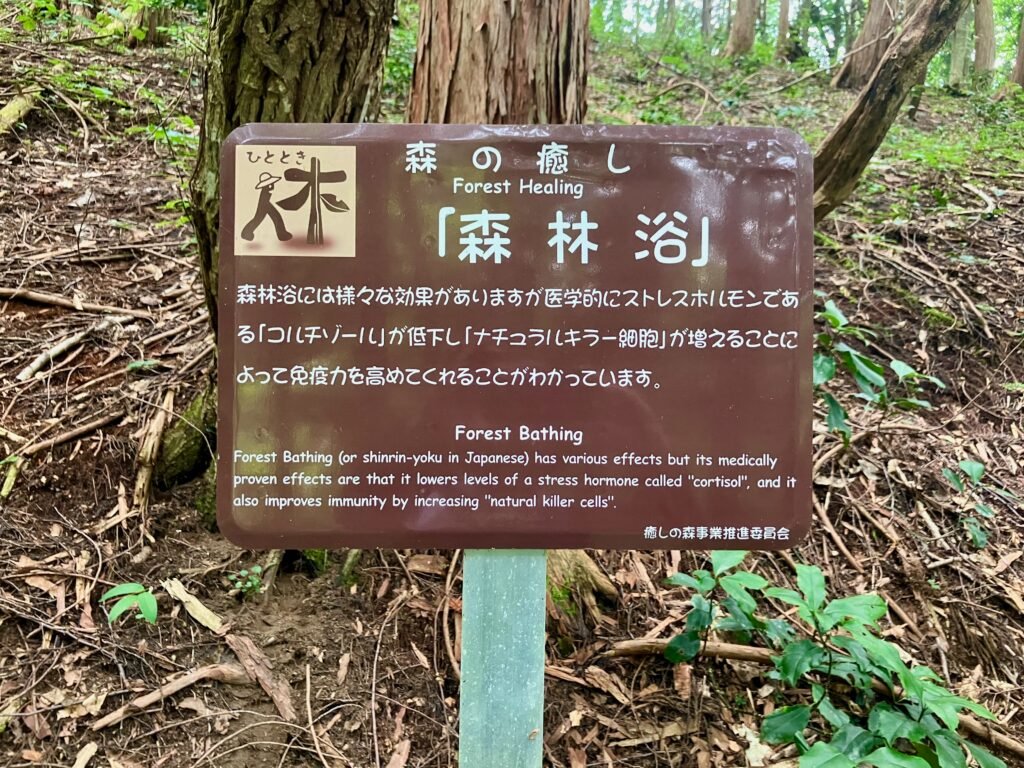

Forest healing, forest bathing, or Shinrin-yoku (森林浴), does more than just “feel good.” Controlled trials show it lowers cortisol, the hormone that spikes under stress, and boosts natural killer (NK) cell activity, a key pillar of our innate immunity. [1, 12]

Immersing ourselves in a forest triggers a cascade of positive physiological events. By breathing the forest air, soaking up leaf-filtered sunlight, and listening to the omnidirectional soundscape, we initiate a powerful mind-body response. Cortisol levels fall, and Heart-Rate Variability (HRV)—a measure of the variation in time between each heartbeat—rises, indicating a shift toward a relaxed state. [1] Simultaneously, our NK cells become more vigilant. [1, 8, 10]

The soft, irregular chorus of rustling leaves and distant birds engages the parasympathetic nervous system, which slows our breathing and ushers the mind into a meditative state without effort. Sunlight, softened by the canopy, delivers a gentle dose of vitamin D while reducing glare, helping to regulate our circadian clock and improve sleep quality.

Forest Curtain – The Science of Light

Leaves as Nature’s Light-Filter

- Broad-Spectrum Attenuation: A mature leaf does not let the full solar spectrum pass through. Spectrophotometric measurements show that a leaf absorbs roughly 80% of incident radiation in the photosynthetically active range. [2] The remaining 20% is reflected or transmitted, creating a uniquely altered light spectrum.

- Natural UV Protection: Pigments like carotenoids and flavonoids in the leaf’s epidermis act as photoselective filters. They strongly absorb blue and ultraviolet (UV) photons while allowing longer wavelengths to pass. [2] This protects both the plant’s tissues and our skin and eyes from DNA-damaging UV-B radiation and the harsh glare of short-wave blue light.

- The “Green Window”: Chlorophyll absorbs light most strongly in the red (≈660 nm) and blue (≈430 nm) parts of the spectrum. This creates a relative trough in the green region (≈500–560 nm) where leaf absorption is lowest. [2] Consequently, a forest canopy transmits a soft, predominantly green light. Human photoreceptors are uniquely tuned to this band; green light is perceived as gentle and does not overstimulate the retinal ganglion cells that drive alertness.

- Psychophysiological Effects: Recent clinical work shows that exposure to narrow-band green light (≈520 nm) leads to measurable reductions in anxiety (a 34% improvement) and better sleep quality. [3] While this study focused on migraine patients, the mechanism—promoting parasympathetic tone over sympathetic arousal—is the same one that activates when we stand beneath a green-rich canopy.

Takeaway for Practitioners and Designers

- Preserve Canopy Density in therapeutic forest sites to maximize light attenuation and green-light transmission.

- Use Tuned Artificial Lighting in indoor “forest-bath” spaces. Avoid bright white LEDs and instead use lighting tuned to the green peak (≈525 nm) at a modest intensity.

- Combine Sensory Inputs by pairing the visual green spectrum with auditory pink noise (1/f) to amplify the overall calming effect.

Negative Ions – The Air We Breathe

The pleasant feeling you experience near waterfalls is not a myth. It is the measurable outcome of natural negative-ion generation. [4, 5] These odorless, tasteless molecules are abundant in natural environments, especially around moving water. When inhaled, they influence the autonomic nervous system. [4, 6]

Research suggests negative ions help relax the body and increase alpha-wave production in the brain (associated with a state of relaxed wakefulness). [6] When you pair an ion-rich microclimate with the leaf-filtered, green-dominated light of a forest, you create a multi-sensory environment that maximizes parasympathetic dominance and physiological resilience.

1/f Noise (Yuragi) – The Sound of Nature

In Japanese, Yuragi (ゆらぎ) refers to the gentle, unpredictable fluctuations found in nature. This quality is precisely what makes a forest walk feel “alive” without being chaotic. The rustle of leaves, the murmur of a stream, and the intermittent chirp of a bird arrive from every direction, allowing our brain to construct a rich, three-dimensional soundscape.

A large part of this richness comes from the prevalence of 1/f noise, also known as “pink noise.” Characterized by a power-spectral density that falls off inversely with frequency, pink noise has more low-frequency energy than white noise. [7] This “balanced” texture mirrors the statistical structure of many biological signals. Because our nervous system evolved in a world dominated by this spectral profile, exposure to pink-noise-like sounds tends to stabilize heart-rate variability and lower perceived stress.

Interestingly, one laboratory study found no measurable advantage of pink noise for acute stress reduction when presented in isolation, suggesting its soothing power is most effective when embedded in a richer, multimodal context. [7] This is exactly what happens in a forest. The 1/f acoustic backdrop blends seamlessly with visual fractals (branching patterns), olfactory cues (phytoncides), and tactile feedback from uneven ground, amplifying the calming response.

Phytoncides – The Scent of Healing

When you walk through a forest, you are literally breathing in its immune system. Phytoncides are antimicrobial volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that trees and plants release into the air to protect themselves from insects, fungi, and bacteria. These airborne molecules, which create the characteristic “scent of the forest,” have profound and measurable effects on our own physiology when we inhale them. [8, 10]

The primary components of phytoncides are terpenes such as α-pinene (common in pine trees) and D-limonene (found in citrus and other trees). Research, much of it pioneered by Dr. Qing Li, has revealed several key benefits of exposure:

- Enhanced Immune Defense: Studies show that spending time in a forest significantly increases the number and activity of our Natural Killer (NK) cells. [8, 10] Inhaling phytoncides prompts these crucial immune cells to produce more anti-cancer proteins, such as perforin, granzymes, and granulysin, which are instrumental in destroying tumor cells and virally infected cells. [10] This immune boost can last for several days after a forest visit. [8]

- Stress Hormone Reduction: Forest bathing trips have been shown to significantly reduce the levels of stress hormones, including adrenaline and cortisol, in both urine and saliva. This demonstrates a direct physiological pathway for stress relief that goes beyond simple relaxation. [8]

- Direct Cellular Effects: Specific compounds like α-pinene have been shown in studies to directly enhance the cancer-fighting activity of NK cells, making them more effective. [9] These terpenes also possess anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties, contributing to overall well-being.

In essence, inhaling phytoncides is not a passive experience. It is an active exchange that directly bolsters our immune function and calms our nervous system, making it one of the most powerful mechanisms behind the healing effects of the forest.

Our Ancient Connection to Nature

Humans have spent over 99% of their evolutionary history in natural environments. This long history of living in and with nature, often described by the biophilia hypothesis, suggests that an affiliation with nature is rooted deep in our DNA. [11] For this reason, being in a forest can create a profound feeling of “synchronization” or “comfort,” calming our spirits and restoring our well-being.

The Complete Forest Experience

To fully embrace forest healing, combine your sensory experience with mindful activities. Practice deep breathing, use your senses to touch and taste your environment (when safe), stretch, and walk. When you find a place that feels right, simply relax there for a while. This quiet time spent in nature will calm your spirit and rejuvenate your body.

References

- Wen, Y., et al. (2019). Medical empirical research on forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku): a systematic review. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 24(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-019-0822-8

- Kume, A., et al. (2017). Importance of the green colour, absorption gradient, and spectral absorption of chloroplasts for the radiative energy balance of leaves. Journal of Plant Research, 130(3), 501–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-017-0910-z

- Lipton, R. B., et al. (2023). Narrow band green light effects on headache, photophobia, sleep, and anxiety among migraine patients: an open-label study conducted online using daily headache diary. Frontiers in neurology vol. 14 1282236. 4 Oct. 2023, doi:10.3389/fneur.2023.1282236. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10582938/

- Liu, S., et al. (2022). Associations of forest negative air ions exposure with cardiac autonomic nervous function… Science of The Total Environment, 824, 153885. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35973547/

- Kolarz, P., et al. (2012). Characterization of ions at Alpine waterfalls. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 12, 3687–3697. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-3687-2012

- Pérez, V., et al. (2013). Air ions and mood outcomes: a review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-29

- Orth, G. L., & Thompson, A. E. (2023). Impact of Colored Noise on the Acute Stress Response. Undergraduate Research Symposium, University of Minnesota Morris. https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/urs_2023/2

- Li, Q. (2010). Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 15(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12199-008-0068-3

- Jo, H., et al. (2021). α-Pinene Enhances the Anticancer Activity of Natural Killer Cells via ERK/AKT Pathway. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(2), 656. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22020656

- Li, Q., et al. (2009). Effect of phytoncide from trees on human natural killer cell function. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology, 22(4), 951-959. https://doi.org/10.1177/039463200902200410

- Grinde, B., & Patil, G. G. (2009). Biophilia: does visual contact with nature impact on health and well-being? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 6(9), 2332-2343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6092332

- Hansen, M. M., et al. (2017). Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(8), 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080851