Table of Contents

In 1991, only 1% of music studios were digital. By 2000, this number had risen to 30%

One must journey back to the early nineties; a time I personally remember well, as it marked the beginning of my foray into the intriguing world of music technology and composition. The year was 1990, and in my novice hands lay a newly acquired Yamaha V50 synthesizer; a remarkable instrument in its own right, reflective of the technological marvels of its era. The intricacies of composing for film or music technology were yet foreign to me, a labyrinth unfathomable. Despite this, like the explorers of old drawn to the mystery of the enigmatic horizon, my curiosity piqued.

Quick to learn and eager to explore this newfound realm, I harnessed the power of the V50’s inbuilt sequencer. This technical feature enabled the multi-layering of musical sounds in a manner that was nothing short of revolutionary to a beginner such as myself. Although the process was laborious I meticulously copied and transcribed well-known pieces like Brahms’ Clarinet Quintet, and the catchy theme song from the then-popular TV show, “Jeeves & Wooster”.

As my familiarity with the synthesizer grew, so did my ambitions. I began to compose my own small pieces, seeking to imitate the short but poignant musical scores that were the trademark of television or commercial music. The aim? To create music that was succinct yet evocative, music that could narrate stories within its limited time frame. The thrill of shaping my narratives through the medium of music was an experience that is still imprinted in my mind; a touchstone for the profound bond we share with this universal language.

The Dawn of a Digital Era: Music Technology in 1992

Fast forward a couple of years later, as my exploration of music technology advanced, I found myself building my own personal computers. This newfound skill coincided with a significant discovery – Cakewalk; a pioneering sequencer application that was compatible with Windows 3.1. Finally here was something that brought the ease and power of a graphical user interface (GUI) to music production.

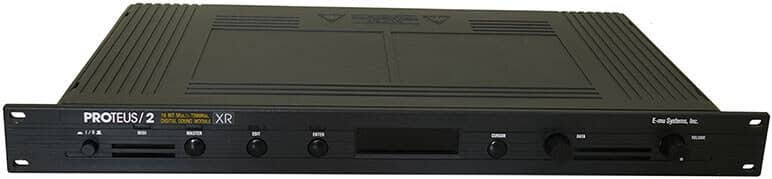

Back in those early days, the world of digital music production was limited to hardware MIDI tone modules and synthesizers. I owned a keyboard, the iconic V50, which played the role of a MIDI instrument that enabled control over my compositions. Yet, it was the orchestral sounds of the Proteus 2/XR created by E-MU that truly broadened the horizons of my musical capabilities.

The Proteus, while offering dry sounds with no reverb, offered the most realistic imitation of acoustic orchestral instrument at the time. Its send/return sockets allowed for the integration of a hardware digital effects processor, for which I chose a budget model provided by ART. This palette of sounds infused a new vigor into my compositions, breathing life into the melodies and expanding the sonic landscape of my works.

From TASCAM DA-88 to Pro Tools: The Journey of External Recording Equipment

In the year 1997, an opportunity presented itself in the form of a film and television composition course at the esteemed London College of Music. That epoch was still dominated by an older recording technology, particularly the use of Digital Tape Recording Systems (DTRS). These studios were outfitted with devices such as the TASCAM DA-88, a machine that was responsible for the initial entrée into the world of studio recordings, captured vividly on DA-88 tapes.

In 1997, Pro Tools|24 was released, which was the first version to support 24 tracks of audio. This was a significant milestone as it offered increased processing power and 24 tracks of 24-bit audio. The same year, Digidesign also introduced the Pro Tools Mix system, which increased the processing power and track count even further.

This era of music production also brought distinctive challenges arising from the need to synchronize video to the playback of audio. To accomplish this feat, a visual medium such as a VHS video tape had to be “striped” with a Linear LTC SMPTE timecode, a distinct audio signal embodying critical time measurements: hours, minutes, seconds, and individual frames. An additional piece of hardware, exemplified by the MOTU MIDI Timepiece, then played a crucial role. This unit had the function of decoding the timecode and serving as the master clock for your sequencer, keeping pace with the video and synchronizing the playback on the computer.

Riding the Wave of Transition: From Hardware Synthesizers to Virtual Instruments

While everything was locked to a master clock by hardware like the MOTU MIDI Timepiece, another new class of outboard gear was making waves in the studios of composers and music producers – the hardware sampler. Coming to the forefront as the next big thing of the era, these devices offered a tantalizing capacity that was akin to an alchemist’s dream. Housing an increasingly diverse library of sampled instruments, hardware samplers like the E-mu ESI-32 buoyed the aspiration of achieving unprecedented realism.

The allure of these devices lay in their unique ability to bring actual recordings of real instruments into the grasp of composers. We now had the power to trigger these accurate, high-quality samples using a keyboard, effectively blurring the line between the sound and the physical instrument. This evolution in music technology symbolized a significant leap forward in refining the auditory experience and imbuing it with a degree of authenticity unheard of in previous eras.

The surge of enthusiasm for hardware samplers was mirrored by advancements in data interfaces. SCSI, or Small Computer Systems Interface, became the standard connection of the times. Enabling faster and more efficient communication between devices, it complemented the use of hardware samplers effortlessly. My own setup constituted not just the sampler but also a SCSI CD drive and an Iomega Zip drive.

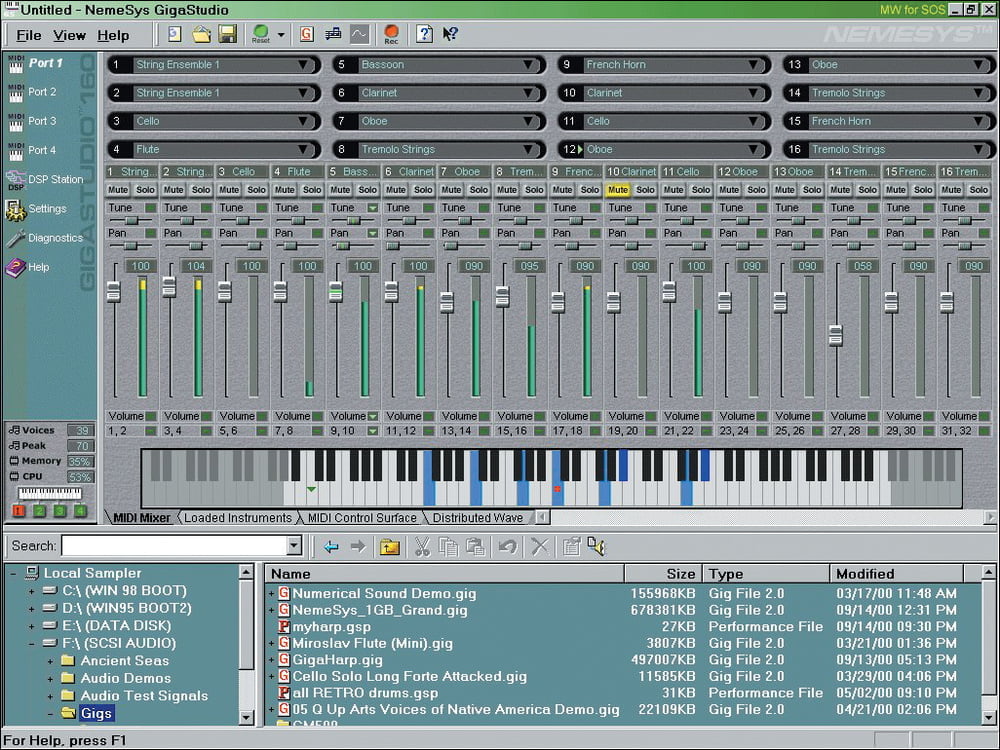

However, the reign of this technology proved short-lived as the computation capacities of computers began expanding at an extraordinary pace. The RAM memory of computers experienced a significant increase, while the hard disk drives started operating at unparalleled speeds. As we approached the turn of the millennium in 1998, Nemesys introduced GigaStudio, marking the inception of the first software sampler.

Purposely built to capitalize on the evolved computer capacities with the ability to use a gigabyte of RAM and even more, GigaStudio was quite a leap from the 32 megabytes that were previously utilized on the hardware sampler. This amplification in the size and potential quality of the sampled instruments unlocked a whole new marketplace for sample libraries specifically crafted for the software.

Some, like the illustrious composer Hans Zimmer, were quick to perceive the transformative potential of this emergent technology. Zimmer’s substantial budget facilitated an innovative setup – a room filled with computers, each dedicated to running an instance of GigaStudio, thus creating an intricate, virtual symphony of quality sounds. Pioneering such a novel application of technology was representative not just of Zimmer’s ingenuity, but also indicative of the sizable strides being made in music technology during this period.

Galloping ahead with the inevitable march of technological progress and perpetual innovation, those of us in the composing and music production leagues faced a financial hurdle of substantial magnitude. To remain competitive and conversant with the times, a significant investment was called for. Not only did we need to acquire the latest computer hardware with sufficient computing power to handle the increasingly sophisticated software, but a litany of eclectic sample libraries also began to raid our wallets.

These weren’t just any sample libraries; they bore the names of esteemed musicians and composers. Entities such as Dan Dean’s Solo Woodwinds that provided the mellifluous tones of meticulously recorded wind instruments; or London Orchestral Percussion which threw open the doors to the rich timbres of grand orchestra percussion sections. Let’s not forget the Miroslav Vitous Symphonic Orchestra, a venerable gathering of robust string, brass, woodwind, and percussion sounds, or Peter Siedlaczek’s Advanced Orchestra, a treasure chest brimming with an impressive variety of orchestral colors and textures.

Digital Audio Workstations: The Backbone of Contemporary Music Production

During this dynamic era, sequencers like Cakewalk morphed into advanced versions like SONAR, capable of etching audio directly onto the computer’s hard disk. I recall the time when I transitioned to Steinberg’s Cubase, a product with a distinctly professional veneer. That transition ensued in tandem with the augmentation of my studio setup, which welcomed the addition of twin Sydec Soundscape Mixtreme PCI soundcards.

These savvy cards featured onboard processing, thus enabling me to deploy plugins by TC Electronics including an immersive reverb and an astute mastering finalizer, all without the taxing drain on my computer’s resources. Even as we reminisce about this challenging period, there’s no denying the exhilarating sense of exploration and revolution that survived even through the toll on our bank accounts.

In July 2008, Nemesys Music Technology, the company behind GigaStudio, ceased operations. This allowed competitors such as Native Instruments’ Kontakt to take over the market share and in time other software solutions, such as the Play Engine from East West Studios, LA, materialized and took the reins. As these new iterations weaved themselves into the fabric of the music industry, sample libraries began to elevate in complexity, putting increasingly significant demands on our workspace computers. Reflecting on this phase, I remember the year 2010 when I was juggling a modest template on a trio of computers. All of them bore the weight of these ever-growing sample libraries.

Unlocking the Power of Pro Tools: A Game Changer in Music Production

In 2007, like a rite of passage, a benchmark in my personal music history was emblazoned onto my career. I had the honor of tracking my first recording at the legendary Abbey Road Studios, partnering with the international symbol of cultural richness, the London Symphony Orchestra. We orchestrated a symphony of sound, eschewing tradition, and instead embracing the cutting-edge music technology of the time.

Enabling our creative exploration was the high-definition Pro Tools system, a veritable titan in the technological chronicles of the industry. Supporting a sampling rate up to an impressive 192 kHz and a powerful 48-bit processing, this formidable system became the backbone of the recording. Coupling the rich symphony with a tool of such precision and power created an experience that was truly unparalleled.

By 2010, 85% of music producers used a computer as their primary instrument

Over the years, Kontakt has continued to evolve and improve, with Native Instruments regularly releasing updates and new versions of the software. Today, it remains a staple in the music production industry, used by composers and producers around the world.

The Power of Computers in Modern Music Production

The narrative continues to my subsequent eight-year tenure in Los Angeles, where I migrated along with my sophisticated tech arsenal. In 2024, I live in Japan and to visualize the turn of events, imagine that earlier arrangement of multiple computers now condensed into one solitary, yet mighty, machine. This solitary beast, equipped with the latest Intel processor, boasts an impressive 64GB of RAM and uses exclusively Solid State Drives for all of my libraries. The logic behind this revolution? Better efficiency and enhanced productivity, all wrapped up in a cleaner, streamlined environment. What a fascinating journey the evolution of music technology has been over the past few decades!

Pingback: Scoring Success: A Guide to Starting a Career in Film Music Composition – Mark Slater